Review of The Confidence Game: Why We Fall For It…Every Time. By Maria Konnikova.

Published on April 1, 1857, The Confidence Man, by Herman Melville, ends with “the cosmopolitan” telling his companion on the steamboat Fidèle that the lack of confidence “these days” is due in no small measure to the “Counterfeit detectors you see on every desk and counter. Puts people up to suspecting good bills. Throw it away, I beg, if only because of the trouble it breeds you.” As “the waning light expired,” the cosmopolitan led the old man away. “Something further,” Melville predicts, “may follow of this Masquerade.”

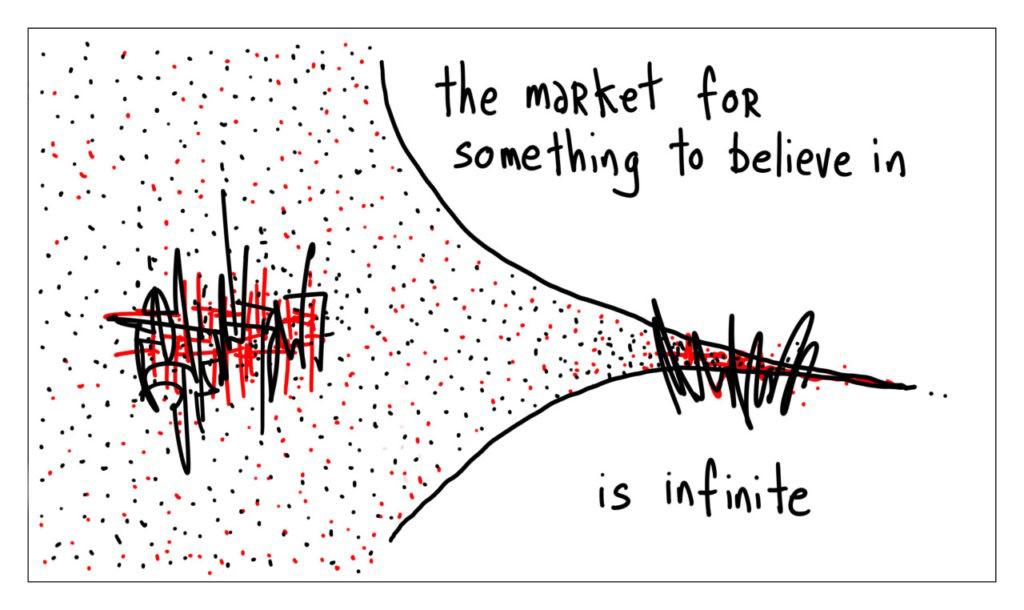

In a world where deceit often masquerades as faith and cynicism as philanthropy, that “something” just might be a con game. And, Maria Konnikova reminds us, con artists, the practitioners of “the (real) oldest profession,” continue to exploit our tendency to overestimate our intelligence and judgment, to believe that we deserve good fortune, and to hand over lots of money to a smooth-talking stranger.

In The Confidence Game, Konnikova (who holds a Ph.D. in psychology, is the author of Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes, and writes a column on psychology and culture for The New Yorker) describes the experiences of dozens of con artists and examines the psychology of their victims.

Konnikova is a gifted storyteller. Her book contains a fascinating cast of characters. Impersonating Dr. Joseph Cyr, a surgeon in the Royal Canadian Navy, Konnikova reveals, Ferdinand Waldo Demara operated on 19 wounded Koreans in 1951 – and took on dozens more identities in the ensuing decades. Oscar Hartzell inveigled 70,000 investors in a con to recover the inheritance of Sir Francis Drake. Glafira Rosales enlisted the preeminent Knoedler Gallery in selling fake abstract expressionist paintings for millions of dollars. And Samantha Azzopardi adopted over 40 aliases over 25 years, including an appearance in Calgary, Canada as Aurora Hepburn, the non-speaking 14-year-old victim of abduction and sexual assault.

In what constitutes a virtual primer of concepts in cognitive psychology, Konnikova draws on a spate of studies to explain why we are so susceptible to scams like these. A necessity for infants that is also conducive to better health and happiness for adults, trust, she points out, “is the more beneficial evolutionary path.” And when our emotions are aroused, they tend to trump reason.

Jagmeet Singh has targeted Justin Trudeau for over a year now & that's politics but make no mistake, what comes aro… https://t.co/KAHKU15IlT

— kris meloche Fri Sep 10 12:11:01 +0000 2021

Other factors increasing our vulnerability include the “Lake Woebegone Effect” (an unwavering commitment to the notion that we are better than almost anyone else); “confirmation bias” (a predisposition to process evidence to support what we already expect to be true); “positivity bias” (confidence that good things will happen to us and we will manage to avoid bad things); “cognitive dissonance” (a predilection to ignore disconfirming information); “momentum theory” (a decision to move forward despite obstacles); “motivated cognition” (the process by which our views are reinforced by self-serving biases in perception); and “anticipated regret” (that generates a reluctance to relinquish a chance of “winning”).

Konnikova also debunks the folklore about our capacity to detect deception. Gaze aversion, nervousness, fidgeting, flushing, hemming and hawing may fit our preconceptions of how liars behave, but these behaviors and lie detector tests are not reliable indicators of deceit. In one study, in which over 15,000 subjects watched video clips of people either lying or telling the truth, only 55 percent identified the honest individual. Alas, then, there is “no Pinocchio’s nose.”

The Confidence Game is not without flaws. To her credit, Konnikova acknowledges that it is difficult to generalize about archetypal victims or con artists. At times, however, her claims seem a bit facile. She suggests, for example, that emotional impressions are irrevocable. She claims that Samantha Azzopardi’s lies were “a deliberate choice,” made “for a very specific reason: personal gain, whether it be financial or other,” though she does not specify the gain — and notes that “some might call Sammy a pathological liar.” Most important, Konnikova does not examine critiques of the principles of cognitive psychology she cites (and others) or traits that might help a possible “mark” from falling prey to the blandishments of con artists.

Indeed, Konnikova doesn’t provide much guidance about how to resist emotional manipulation. She urges readers to “know yourself well enough to recognize and control your emotional reactions; stay grounded in details and logic; identify people you trust and the “triggers” that tend to trip you up; define, preferably ahead of time, how much you are willing to invest (materially and emotionally), boundaries you won’t cross, and an exit strategy. Although they are utterly unobjectionable, these recommendations are, of course, easier to articulate than implement.

For this reason, perhaps, Konnikova concludes with the rather odd (and un-Melvillian) claim that con artists, at their best and worse, and, of course, inadvertently, give us a sense of hope, faith, and purpose, and teach us that those who are miserly with their trust end in despair.